By Mónica Lavín

Christmas, with its raspy voice,

knocks on the stomach’s docile door.

Behind the glass, misted up by the cold,

the shop windows display all the masterpieces of gluttony.

Manuel Gutiérrez Nájera, Mexican XIX century author

Part I: Introduction

Christmas parties in Mexico are a time of celebration where the ritual of the annual feast is dressed up in food. The Catholic commemoration of Christ’s birth was incorporated into the Pre-Hispanic ritual during which December 26 –the sixteenth month of the Aztec calendar- was the celebration of the descent of the God Huitzilopochtli and the invocation for rain in spring: the atemortli.

The Aztecs practiced auto-sacrifice during this ritual, wounding themselves to obtain blood from tongues, ears, calves and other body parts, this way gods wouldn’t get angry, after which they offered and ate corn tamales and vegetables. They couldn’t eat anything that wasn’t the food prepared especially for the occasion, and spent the rest of the night in vigil, with campfires to withstand the cold of the temple’s patio.

The religious spirit, the veneration of the gods, the offerings, and the rituals were already part of the culture of the people conquered by the Spaniards, who with time adapted and modified their celebrations to conform to the canons of the new culture, and even though during the first years of the Colonial era in many regions of New Spain Christmas was celebrated, following the Catholic tradition, with a diet of vigil in which there were no meat dishes, the Christmas fare -be it the Christmas Eve supper or the Christmas Day meal- that evolved in the following centuries reflected a mix of both cultures’ own cuisines.

Today, you can enjoy on Mexican tables, with regional variations, a Christmas menu that reflects this cultural fusion, although in large cities parts of the population are more inclined toward the European customs.

Aperitif: Posada Food

Christmas celebrations in Mexico start with the very Mexican posadas, created in Colonial times by the priests during their evangelization process, which together with the pastorelas -plays enacting the battle between Good and Evil, also intended for instruction-, took root in our country.

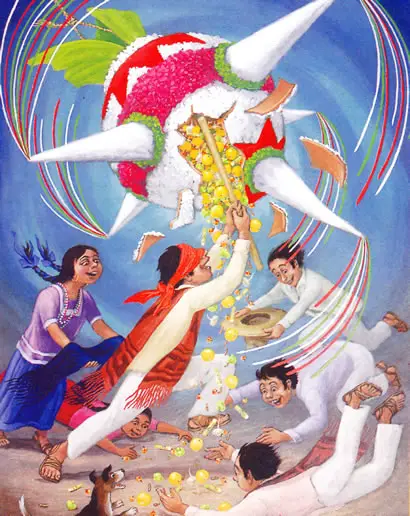

The posadas begin nine days before the birth of Christ and reenact Mary and Joseph’s journey to Bethlehem. They are celebrated among neighbors, in schools, workplaces, private homes, where the tasks are distributed among the participants.

Between reenacting and striking the traditional piñata -that originally had seven points like the seven deadly sins-, abundance spills from the belly of the decorated pot, from its fall seasonal fruits: tejocotes, sugar cane, peanuts, and mandarins. These fruits -with the exception of the peanuts- are the main ingredients of the delicious punches that warm up the body on the cold nights of the merry celebrations.

Served in little clay jugs, the Christmas Punch -which can have some piquete or sting, that is, spirits, if the guest so desires- has that sweetness that is so typical of these seasonal celebrations. The beverage is sweet and is drunk by sips and spoonfuls, since the pulp of the fruit, macerated by the sugar and the boiling, falls tastefully apart in your mouth.

The pinata’s fruit basket provides the peanuts -one of Mexico’s legacies to world cuisine- that are cracked open and eaten all night to keep the guests awake and entertained.

Tamales are usually the main course posadas. They are removed steaming from huge pots or steamers. Every region individualizes this food wrapped in corn or banana leaves by adding the meat, fish or vegetable and sauce from the region. Tamales are the itacate of Mexico’s ancient inhabitants. Itacate, the Aztec word (iztacatl) for provisions, is a food carrier for which neither plate nor silverware is needed.

Romeritos and pre-hispanic flavors

One dish is without a doubt authentic proof of the survival of ancient flavors, the romeritos, which are an extremely Mexican part of the Christmas celebration and prove the ancient inhabitants of the Valley of Mexico’s knowledge of nature. The romeritos (which are not romeros nor Rosemary) are plants that only grow in the winter months in the brackish soil of the former Texcoco Lake. Faithful to the Great City of Tenochtitlan’s swampy origins, the romerito is a wild plant that doesn’t need to be cultivated and that is gathered manually.

Meaty and green, its short needle-shaped leaves release their flavor in a dish that combines them with nopales -a Plateau cactus- and dry shrimp patties in a mole based sauce. Anyone who has tasted romeritos knows that they are being faced with a historic wonder of Mexican cuisine.

Their crisp, salty flavor reminds us of the valley’s marshy origins and allows us to converge with our past while taking us to the superposition of times and to the combination of Aztec ingredients with New Spain’s invention: mole. The taste of a romeritos taco is communion with history and the land, in a Christmas that is renovated year after year.

The combination of various tubers and fruits, many of Mexican origin, is called Christmas Salad. The basis is jicama -a native of Mexico-, which yields the whiteness of its biteable and crispy pulp to the deep red of the beet (without a doubt of European origin: sugar was obtained from beet before sugar cane was introduced by Marco Polo), to which pieces of celery and apple are added, and chopped peanuts sprinkled over.

Sweet Christmas Finales

The Christmas feast is prodigious above all in sweet finales. From Spain, we also inherited the custom of ending the feast with marzipans and almond pastes (turrones) that were customary fare in the Spanish Peninsula and which Hernando Cortez had already included in his first banquets.

The marzipans were brought all the way from Spain since their almond dough -an Arab legacy- allowed them to last quite some time. Afterwards, the convents in New Spain adopted the confectionery activity using European pastry books and adding -with local natural ingredients- their own recipes and variations. Thus, the marzipans, made with egg, almonds, and sugar, were prepared in large copper pots and adorned the Christmas celebrations.

The preparation and selling of pastries and candies were allowed at the convents, also as a source of income. The almond paste from the Spanish regions of Jijón or Alicante could also be prepared in Mexico if a sufficient supply of almonds was brought overseas. But it was above all some exiled Spanish families, who came to live in Mexico in the decade of the 1930s, who continued the tradition of making marzipans and almond pastes -as is the case of the almost sixty-year-old family business of Mazapanes Toledo-, so these sweets would never be missing on Mexican tables. Many Mexican regional sweets are derived from this imported confectionery that later took root in the convents. The pepita fruits of Puebla, finely molded from a sugar and pumpkin seed paste, are a local variation of Spanish marzipans.

In some regions of Mexico, the buñuelos (fritters) are the most appreciated Christmas sweet. They can be enjoyed, dipped in caramelized sugar honey, in plazas and arched portals. In the city of Oaxaca it is customary, after eating the honeyed buñuelo, to throw the clay plate on the floor or against the wall so it breaks into little pieces. It is part of the season’s ritual of annual renovation.

Once the Christmas supper -or meal- is over, everyone’s heart is content. Outside, the winter cold chills the bones, but inside the homes the warmth of family and friends and, of course, of the delicious Mexican victuals that were just enjoyed, allows the celebration to continue.

Last Updated on 22/07/2022 by Puerto Vallarta Net

Leave A Comment