By Monica Lavin

The origin of Mexican Sweets and Candies

Mexican confectionery, still so popular today, was created in many monasteries, amidst the lull of prayers and songs in the enclosures’ freshness .. . under the Carmelite, Dominican, Theresian, and Hieronymite vestments.

The stone metates, molcajetes and mortars for grinding and pounding, wooden molinillos or hand beaters, along with an acute reverence for the chemical processes involved and the constant quest for new shapes, colors and flavors, the colorful and sweet mosaic of our rich and baroque Mexican candy was created.

There are many reasons why this activity thrived among the 15 or 20 religious orders in the middle of XVII century in New Spain’s capital, they needed to find ways to repay their benefactors or to sell their products thus providing financial support to monasteries and the thousands of women cloistered within.

It was female hands, hands that kneaded dough under the conviction of faith, – or by fate placed on them by relatives or simply to give wings to their seclusion, they toiled and created such a rich catalogue of the sweets, that still today we feel proud to find these creations in candy stores such as the old “Dulcería de Celaya”, on 5 de Mayo street in the centre of Mexico City. Within the limited space of the monasteries, nuns discovered a definitive way of signing their legacy: Candy-Making.

It was the colonial era, and in this country, New Spain, cross-breeding took place in every existing domain: Language, engineering, religious rituals, descendants, Spaniards, Creoles, mestizos, and indigenous groups all lived together.

Dining was a daily ritual, so it was at the heart for both wealthy families and monasteries, where Spanish, Creole, and Indian women met, it was here where Mexican food was born: A cross-breed by definition, unique and imaginative due to geography and desperation.But it was at the fireplace, where crossbreeding was practiced daily. It was there that products from the Old Continent and America inevitably converged trying to recreate dishes that resembled the Spanish traditional ones, but with the new flavors obtained from tastes and colors of this tropical location.

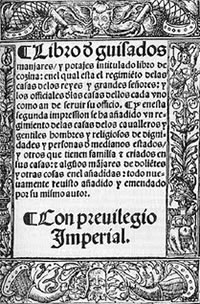

It was at this intersection, where two culinary traditions, on one side the indigenous people with their distinctive flavours and different ingredients, and on the other Spanish cuisine, enriched by the newly printed Libro de los guisados y manjares del cocinero real Ruperto de Nola (The Book of stews and delicacies by Ruperto de Nola, the Royal Cook), that Mexican cuisine came into existence.

Our confectionery is a different kind of Mexican baroque: Its whimsical expressions, the exaltation of form and taste, its vitality due to a wide repertoire brought from Asian countries and renovated with Mexican fruits and spices. Octavio Paz wrote: “There is a relationship between Creole sensitivity and baroque, both in architecture as in the literature, and even in others, such as the kitchen.” It is a symphony of flavors and sensations that are named within Mexican candies. Sweets such as the gaznate (windpipe), the jamoncillo (small ham), the beso (kiss), or suspiro (sigh), reminds us of secret desires and common feelings, as candy production, which required different hands, and processes and had to transcend the high walls of monasteries.

The enjoyment of honey was deeply established in the tastes of Mexican territory inhabitants long before the arrival of sugar, as was among world nomadic tribes in all areas where honeybees were found. When the Spaniards arrived, beekeeping was a well-developed local activity, since many of the ritual delicacies of the Mayas and Aztecs were made from corn and bee or maguey agave honey. This is the case with the familiar alegría (joy) or tzoalli, a sweet that we can still enjoy today, made with toasted amaranth seeds and honey. Maguey honey was an important sweetener: The Aztec capital Tenochtitlan would receive a tribute of 2512 pitchers of this sweetener from the Maguey producing regions every 80 days.

Without the sugar cane that Europeans brought to America, which had in turn been brought to Spain by the Arabs all the way from India, sugar production (also Arab methods) would have been impossible. Sugar was the main candy ingredient and basic by its very nature.

The Conquistador Hernando Cortez was the forerunner of sugar cane production as he planted it in his country estates in Tlaltenango, Puebla and The Tuxtlas, Veracruz. Crops later spread to Guerrero and Morelos, and Mexico’s Central Valley. The production of molasses in rudimentary sugar factories changed many of the indigenous recipes and opened the road for confectionery and pastry making.

Mexican candy contributions & the fusion process

Sugarcane cultivation meant big changes in the economy and landscape, as well as family structure, legislation, and the mestizo tastes and gastronomy. Few products have had such an impact on the culinary history of sugar. The sugar cane plant found, in Mexico’s tropical lands, suitable conditions for its widespread growth. If you had access to chicken eggs (of Hindu origin, also a contribution of the conquistadors) and the excellence of the aromatic Mexican elixir, vanilla, to experiment with new flavors.

Vanilla, a species belonging to the orchid family that Mexico contributed to the world, was already used in these lands as a flavoring, as a perfume and medicinal tonic base. Because of its importance, it was also used as a tribute to the pay rulers. During the XVI century factories in Spain made vanilla-flavored chocolate. Strangely, for centuries, Mexico held the hegemony in vanilla cultivation, as its pollinating agents- the Melipona bees and a specific hummingbird were found only in Mexico.

Originally introduced from Ceylon, cinnamon was another contribution from the European continent, where the Andalusian and the Romans had enthusiastically used it. Almonds and nuts came from overseas and found substitutes or new ingredients in peanuts and pumpkin seeds, both of American origin. The abundance of fruit, captured in preserves and sugar-coated fruit, was re-created in the pumpkin seed marzipan in convents in Puebla, where colorful pineapple, mameyes and Zapote (Sapodilla) were eagerly consumed in their candy versions.

Chocolate was without a doubt the most outrageous food contribution from the pre-Hispanic cultures to the Europeans. Prehispanic Indians traditionally drank the brew as a bitter drink.

During colonial times, chocolate drinking became a true passion which came to “jeopardize the conduct of Catholics before the ecclesiastical authority.” Consumption was therefore prohibited or rationed in some monasteries, in others nuns gave signs of chocolate-making skills. Women drank it during mass. In Chiapas, it’s said that a bishop who condemned the use of chocolate during mass, was later found poisoned in his home.

Chocolate, whose taste and aroma ruthlessly transgressed and attracted mids that were otherwise sound, went beyond the liquid form and in time infected pastries and candy making. But despite adding sugar, cinnamon, and vanilla to chocolate in the XVI century, chocolate wasn’t used in candies and baked goods, until recently, and after it was used in such a manner on the European continent.

Candy ingenuity was largely a result of trial and error and observation of the mutation of certain properties of sugar that became liquid with water and caramelized with fire, egg whites, which inflated with air, and egg yolks could be used for mixing and varnishing.

Mexican Candied Favors

Artemio del Valle-Arizpe, a chronicler of the colonial era, wrote about St. Jerome Monastery, founded in 1585 and known for its pastries:

“Your candy is a wonderful, Summit and Emporium of the monastery: The traditional Moorish Alfajor, their lady fingers and susamieles, their caramelised egg yolk candies wrapped in colourful paper .. . all looks like strange flowers, their little egg-shaped candies, their alfeniques, hallelujahs, and cactus candy, their refulgent bites of sweet potato with pineapple and almond, or orange or apricot, their blushing pine nut panochitas, their most excellent petretes, their butter cakes, their angel’s trill, their stuffed Paschal cakes, and their paper-covered sweets with Baroque cinnamon drawings, which surpasses every taste and aroma.”

These candies the nuns created, helped put them in a position where they could be very close to the spheres of power. The Convent of Santa Teresa, for example, the nuns offered hot, frothy chocolate, turn-overs, and sponge cake to friars and politicians, that, while dipping them in chocolate cakes, took many important decisions. The Hieronymite Abbey has received frequent visits from such famous personalities as viceroy, his wife and their escort, bishops, and philosophers. Meetings with music and poetry readings were held, during which, the court and religious dignitaries, tasted delicious pastries and preserved pumpkin candy. Thus, either as collectors or channels through their education or as producers with their candy, monasteries were the main and most active centers in the colonial era.

Mexican Regional Candy

The nuns’ efforts, which gave the candy manufacturing its distinction and its range of forms, names. and tastes, turned Mexican candy in a sweet habit that, after Mexico’s independence, would find its way out and into the confines of the homes, then the street and eventually factories. Before this happened, it had to travel the road to regional areas and specialization. Many monasteries were distinguished by their sweet specialties, particularly those of Mexico City, Puebla, Queretaro, Oaxaca, Chiapas, Michoacan, Yucatan, and Veracruz, many of which reached great heights in candy confection.

The presence of monasteries in the capitals of the provinces was one of the leading causes of specialized regional production. Sweet production in each monastery acquired its own identity. The sweet potato candy, or camotes, originally made in the monastery of the Clarisas in Puebla, for example, became the traditional sweet of that State.

Production of sweets ceased to be exclusive to the monasteries when sugar consumption became popular, the guilds began to expand, small factories were established and sweet production started in homes. So confectionery, with twists and turns, along with an ever-paler role of nuns in educating the young ladies, finally transcended the monastery walls. Candy-making techniques and recipes were relegated to shelves and old books, among other bits of wisdom bequeathed to future generations.

Consequently, the independence and political reforms of the XIX century in Mexico, and later with the urban and industrial development of the next century, the Baroque candy zeal went all the way from a homespun catalog filled with desires to a more mundane activity.

Paletas and Mexican sweets

Hence it is possible for the palate to get a sweet and diverse impression from every region within Mexico: The coyotes from Sonora, the Glorias, palanquetas and nut rolls from Nuevo Leon, the ponteduros from Sinaloa, from Durango the mostachones, from Jalisco, cocadas, capirotada and arrayan or myrtle candies. Colima has alfajores, Michoacán, cueritos, ates, and morelianas, Guanajuato offers charamuscas and cajeta; San Luis Potosi, prickly pear cheese, trompadas, wafers and custard, Puebla has camotes, tortitas, egg white duchesses, brides, little kisses, and canelones, the State of Mexico tempts you with alegrías and meringues, and Chiapas has nougats and alfeñiques, among many other regional sweets.

Last Updated on 21/02/2021 by Puerto Vallarta Net

Leave A Comment