Huichol Art Deer

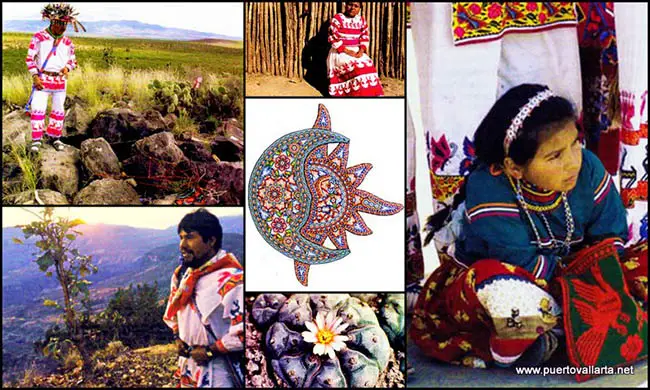

In the southern part of the Western Sierra Madre highlands, there is a region known as the Grand Nayar. There, on both sides of the Chapalagana River Canyon, among deserts, mountains, and valleys that join the states of Jalisco, Nayarit, Durango, and Zacatecas, live the Huichol or Wixarika people, one of the most important indigenous groups in Mexico.

Those of us familiar with their exquisite folk art creations know that theirs is an ancestral art. It is an art that narrates, sings, provokes… an art that makes one imagine dialogues, dances, confrontations, mysteries, since all their images and designs, no matter how simple they seem to be, have one common characteristic: they all tell stories.

Nothing is gratuitous in Huichol art. Every pattern, color, and stroke has a meaning. They’re enigmas that can only be deciphered by the observation, sensitivity, respect, and wisdom of these mystical people.

Wixarika Art

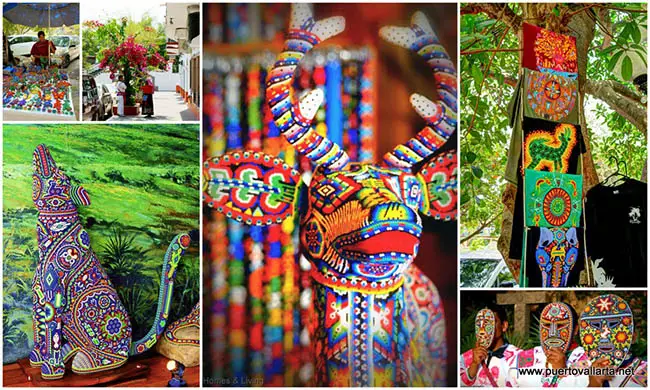

Their tsikuri or eyes of god, their yarn-decorated tablets, their gourds and masks covered with multicolored beads; their embroideries and arrows; their music and dances; their body paint, garments, hats, necklaces, and bracelets… all have a hidden phrase, a secret passage, a story to tell.

Wixarika art is a conceptual continuation of existence. It is the collective memory of a people trapped in colorful yarns, of nature captured in beads, of the vital energy of their religion expressed in abstract designs.

Five Cardinal Points

In order to understand the profound meaning of Huichol art, it is necessary to understand their complex cosmogony and, at the same time, the territorial limits set by their geography.

In the Wixarika people’s map there are five cardinal points: to the west, Isla del Rey, in San Blas, Nayarit; to the south, Isla de Los Alacranes, in Chapala Lake, Jalisco; to the east, El Quemado mountain, in Real de Catorce, San Luis Potosí; to the north, Cerro Gordo, in San Bernardino Milpillas, Durango; and in the center of this sacred universe, Teakata, in Santa Catarina Cuexcomatitlán, Jalisco.

There are at least 24 ceremonial centers or tikupa throughout this large, rough territory. That is where the elders keep the nierikas, a Wixarika word that refers to the aspect, the facade, the external surface, and at the same time to the intrinsic characteristic of things. The nierikas are both the representation of an idea and the reflection of the person who created it. They are ceremonial objects, offerings created by men and women to flatter, give thanks, or request favors from their gods, the elements of nature.

For the Wixaritari (plural of Wixarika), the sun, the sea, the rocks, the earth, the deer, the eagle, corn, peyote… are at the same time the origin of life and man’s companions. They deliver the mandates that guide daily life through the mara’akame, the one who knows how to dream, which is to say, the community’s spiritual leader, he who has learned how to penetrate the sacred world.

José Benítez Sánchez, mara’akame of Zitakua, Tepic, in the state of Nayarit, who in 2003 received the National Award for Folk Art and Traditions because of his exquisite artwork, says that “the nierika is the face of the person, the face of the thing itself. The nierika can represent the Earth’s skin, the face of the sun, of the deer, of fire, or of the peyote, as well as that of the man who makes the offering’.

A nierika is an object that can be created by any believer and can take on diverse shapes. Sometimes it is a tsikuri, a colorful creation also called eye of god, made from strings strung together upon cane grass crosses forming a pattern of one or more diamonds. The eyes of god are used as protection and are particularly made for keeping children safe and healthy. The father makes a tsikuri in which for every year of the child’s life a diamond is strung until reaching five, the Huichol’s magical number… because just as they have five cardinal points, they have five Nakawé mothers, five peyote colors, and five corn colors. There are five rain gods, and it is five times that the mara’akame must make a pilgrimage to Wirikuta, the site in Real de Catorce, San Luis Potosí, where the Huichols meet with their gods to complete their formation and thus reach their religious hierarchy.

Special colors are needed to make a ritual eye of god, because each color also has a meaning. Black is the color of the Tetei Amara, the Pacific Ocean, where the man-devouring snake is found. Blue is the color of water and rain and represents Rapawiyeme or Chapala Lake, the southern region. Red symbolizes the east, the Parietekúa region, where the peyote god lives. The colors thus represent sacred places, specific gods, and particular requests. The colors chosen by the Wixaritari to decorate their nierikas are therefore by themselves the message: through them men petition and speak with their gods.

Feeling color

The Wixarika people experience color in a very particular way.

Color is experience, profound perception, allegory. The selection of their color palette, visual games, and artistic designs has one origin: peyote, the sacred food.

Peyote is a cactacean with hallucinogenic and psychoactive properties whose consumption influences visual perception in a particular way. Thus, the sensations experienced by the Huichols during the ritual consumption of peyote produces an altered perception that is experienced in colors and in full color.

Researcher Ramón Mata Torres wrote the following about one of his journeys to Wirikuta: “The colors are intense and alive. Each can be clearly perceived, and none overshadows the others or loses intensity if it changes place. The lines of color float in space, spinning freely and creating multiple figures. I have never seen such marvels created by color… so much variety in such simplicity! Greens, violets, oranges, blacks, blues, whites, purples, reds, burgundies, yellows…”

Huichol art is the art of color, as it is experienced by the mara’akame in his communication with the gods. In a ritual trance, he receives the gods’ instructions, their mandate, and sings what they dictate. His is the voice of fire, water, earth, the stones, the trees, and the eagle; he is the voice of the divine triad: deer-corn-peyote. When the mara’akame sings, the stories of his people’s origin emerge and the rituals come to life again; all images acquire meaning, and words, force.

If a wixarika becomes mara’akame, it is because he is able to sing the words of the gods. Possessing the gift of interpretation, the mara’akame is in charge, through his and others’ dreams, of finding the paths to follow, the rites that will allow the desired equilibrium, physical or spiritual.

The healing power of the mara’akame is a gift that he is born with, a quality that, according to the custom, obliges him to search for internal growth and to generously offer his services. There are those who are born to say prayers, and must lend their voice to the planting and harvest rituals; others, to be bone doctors, so they have to see to sprains and put bones in place; yet others, to be pus soakers, so they must heal people’s infections. However, he who is born mara’akame has the power to do all that and much more. He can cure different ailments through the smoke of his pipe or by performing cleansings with herbs and feathers, all of which is as important as his work as a prayer singer.

The mara’akame only sings under the influence of peyote, and his songs sometimes turn into color images that tell the stories of his people. These images are recreated in the colors and designs of the Wixarika people’s handicrafts.

Strings that capture time

Although nierika refers to practically any ritual object, this name was originally given to square or round tablets with a hole in the center and decorated with designs made with colored yarn. In ancient times, they were crafted with naturally dyed woollen yarns. During the 20th Century, wool was replaced with cotton and later with industrial yarns. Another change started in the 1940s when the Wixaritari began to migrate to cities, the ritual tablets started growing in size. What was once meant to be an offering was transformed into a simple handicraft, an object you could sell. Modernity and necessity mutated what was originally a nierika, a ritual object, into a mundane sellable handicraft.

Today there are important Huichol art collections that possess unique pieces created by men who transformed the voice of the gods into beautiful, colorful images. Some works narrate the original myths, yet others portray the Huichols’ main festivities, their daily life, and even the healing power of a mara’akame. Most tell about the magic that lives in the peyote, in the deer, in corn, in the eagle, in the rain, in the sun, in the snake …

Although not all handicraft creations are based on the cosmogonic vision of a mara’akame, since nowadays most are made only as mere decorative works, in them the artisans’ creativity, free of its religious burden, expresses the aesthetic balance of a people used to communicate with color, lines, and the figurative or abstract images of their environment.

Gourds, Life Containers

Just as with the small nierika tablets, the rukures, which are gourds covered with wax and nowadays decorated with colored beads, also suffered a series of transformations through time. Long ago, ant-hill stones or corn kernels, bean or pumpkin seeds, small crystal rocks, deer meat or hair, wax figures, and even cotton balls, were glued onto the gourds. First, they sketched the figure with wax, and then they filled it to create the desired images.

These used to be representations of requests, needs, and were deposited in sacred places with the idea that “just as water is drunk out of a glass or food is eaten off a plate, so the gods drink the requests that are put in the gourds, thus more easily finding out what the person wants.”

Gourds are utilitarian articles par excellence. In the Huichol world, they are used in all kinds of ceremonies: to prepare the earth for planting. to propitiate good hunting, to gather peyote, or to make tesgüino, a sacred beverage made from fermented corn and drank by men, women, and children during the Huichol’s main fiestas, called mitotes.

Today, crafted gourds are among the Wixarika’s most popular handicrafts. But the new designs are no longer related to ceremonies and requests. Only the mystery of the patterns, of the figures, and of the combination of colors persist, together with the painstaking precision of the beadwork.

The use of beads was introduced to the Wixarika region in the 20′ century, and since then this material has also evolved. Originally, beads were larger and did not have the uniformity of present-day beads. Today, they can be found in different sizes and in an incredible variety of colors. Some craftsmen, however, make high-quality collectors’ artworks using Czechoslovakian beads, which are smaller, and of course more expensive.

Hand-Embroidered Art

Colored beads are also used by the Huichols to make bracelets, chokers, bags, belts, and earrings, originally meant to complement the traditional garments of men, women, and children. In Wixarika clothing, we can appreciate how the cross-point embroidery is also a way of representing their cosmogony: in it, you can observe their patterns, animals, sacred plants, and landscapes.

When you look closely at the embroidery on the huerurri, Huichol men’s traditional cotton pants, or on the kutuni, their long, open-sided shirt, you discover a world where each stitch and each design recreates this people’s cosmogony. The embroideries on their garments are so important to them that you can even find nierikas requesting god’s fine embroidery work.

Embroiderers put their soul into each creation, stylizing in their own fashion elements that are common to all. The deer, for example, incarnates goodness; the eagle, associated with the sun, is the planet’s supporter; the snake represents the rain; lightning, movement. Not all the elements have a divine significance but are instead the representation of daily life. Dogs, horses, chickens, turkeys, worms, leaves, butterflies, and an endless array of other images enrich the whole.

Using this same mysticism, the Huichols craft their masks, whose ritual use is restricted to the Easter week festivities. The carving of their masks is not very elaborate. Some are painted, others have horsehair beards. Some are decorated with ritual designs, with representations of their main gods, such as Tatei Werika Wimari, the two-headed eagle who keeps watching over the Earth and the Heavens, or the peyote, with its five basic colors, which are the same as those of corn, their main staple: yellow, blue, red, white, and black.

On the contrary, the bead-decorated masks are just handicrafts mainly made to be sold and thus to support their 8 families. The same can be said of some wood carvings, like the zoomorphic figures covered with multicolored bead patterns, like jaguars, iguanas, deer, and snakes, all of them, modern and colorful creations of the Huichol people’s great imagination.

These are, like all Wirarika art, silent but richly visual manifestations of a profound millenary tradition turned into multi-colored art.

By: Alejandra Flores

FURTHER READING

– Huicholes and Pto. Vallarta

– Alberto Ruy-Sánchez Lacy: Arte Huichol. México: Artes de México y el Mundo, 2005. ISBN 9706831142

– Humberto Candia Goyta: Wixárika: La expre sión cultural artesanal como fundamento de desarrollo. México: Zapopan, Jalisco: El Colegio de Jalisco, 2002.

– Mariana Fresán Jiménez: Nierika: Una ventana al mundo de los antepasados México: CONACULTA: FONCA, 2002.

– Ramón Mata Torres: Vida y arte de los huicholes. México: Artes de México. No 161, año XIX, 1960.

– Huichol People on Wikipedia.

Last Updated on 22/07/2022 by Puerto Vallarta Net

i really liked the culture and the art